Undoubtedly, change is inevitable in today’s life. Since development means change and growth, can outside change become the motive to personal development? Defining the term teacher development, it is “the process whereby teachers’ professionality and/or professionalism may be considered to be enhanced (Evans, 2010, p. 131) and professionality in turn refers to “an ideologically, attitudinally, intellectually and epistemologically-based stance on the part of an individual, in relation to the practice of the profession to which he/she belongs and which influences his/her professional practice (Evans, 2010, p. 130).

By Evangelia Vassilakou, MA in Applied Linguistics

Process of teacher development

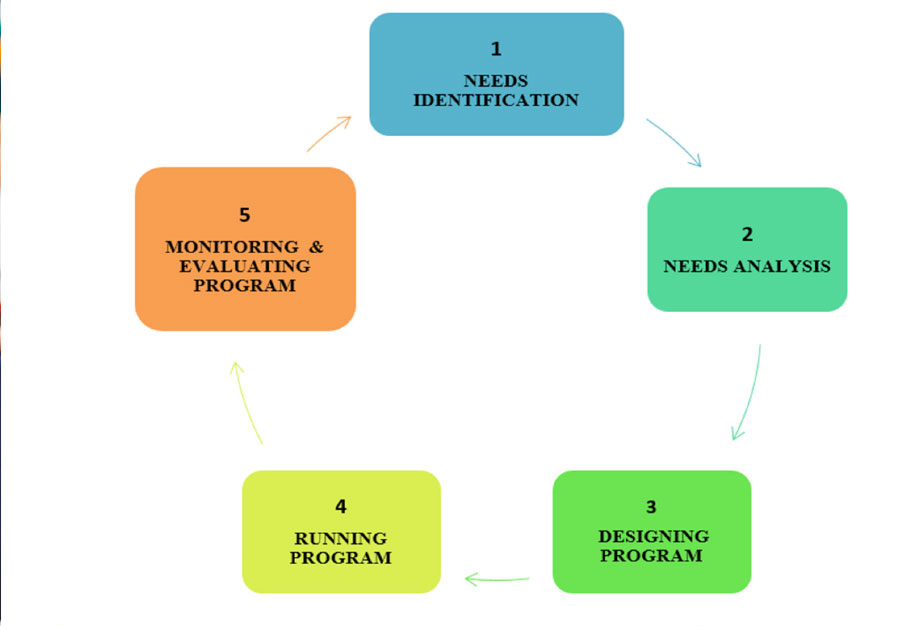

The vast majority of educationalists have thought of the process of teacher development as a cyclic process as shown in figure 1 below:

Figure 1 The School focused staff development cycle by O’Sullivan, Jones & Reid (1988) as cited in Asif & Jabreel, 2014, p. 148

The above cyclic figure is very useful as it facilitates teachers to ask and answer the following questions:

Where are we?

Where do we want to be?

How do we get there?

How will we know when we have got there?

Further elaboration on the stages of the cyclic process

|

1&2 |

Needs identification and needs analysis

A well-structured teacher-development program should aim at a multitude of aspects such as “adding to teachers’ professional skills and their prior knowledge”, “expanding their professional expertise”, “demonstrating a marked improvement in teachers’ performance”, “elucidating their professional values” by remaining “context sensitive”, being in agreement with the teachers’ cognitions or institutional beliefs, “being practical enough”, “being beneficial for each individual teacher”, “giving a sense of achievement”, and “involving a sharing of knowledge among educators” (Glover & Law, 1991; Blandford, 2000; Dean, 1991; McLaughlin & Oberman (1996) as cited in Asif & Jabreel, 2014, pp. 148-149).

{loadmodule mod_random_image,call to action subscribe in articles}

|

3 |

Designing a program

While designing a program, features that should always be taken into account, apart from collaboration, sensitive context and compatibility of the development program with the institutional culture are “the continuity”, the “reflective and analytic” nature of the program, and its “ownership” (O’ Sullivan et al., 1988) ensuring the participation of all teachers.

|

4 |

Running a program

According to O’Sullivan et al., (1988) there are various ways of organizing training courses in a teacher development program such as “external short courses”, attendance on degree/certificate/diploma”, “private study”, “discussion held by experts”, and “coaching”.

|

5 |

Monitoring/evaluation of the program

The purpose of monitoring is to evaluate every step on the cycle of the development process and determine its efficacy. More precisely, “evaluation is a long-term judgment as to the worthwhileness of the staff development events” (O’Sullivan et al., 1988).

The two levels of teacher development

Teacher development can be considered at two levels - the institutional and the individual level. At the former level, teachers may “refine their own knowledge” and try to “adopt changes” or empower “their ability for self-development (McGrath, 1986 as cited in Asif & Jabreel, 2014, p. 151). At the latter level, teachers “are to be trained and developed, rather than to be viewed as people who can and should develop themselves” (Hargreaves and Michael, 1992 as cited in Asif and Jabreel, 2014, p. 151).

A diversity of popular approaches to teacher development

There are certain important approaches to teacher development: a) the client-centred approach, b) the self-development through class observation, c) the self-awareness through groups in teacher development and d) the data-based teacher development.

The first approach is based on learner - centred programs that “incorporate into classroom information by and from the learners” (Nunan, 1988 as cited in Asif & Jabreel, 2014, p. 152). The workshops conducted were the source of numerous client-centred principles where teachers should be encouraged to observe reflect, evaluate and practice their own teaching.

The second approach is based on the idea of turning classroom observation into a tool for teacher development (Wang & Seth, 1997 as cited in Asif & Jabreel, 2014, p. 152). Teachers can also choose both the observer and the item of teaching to be observed for the subsequent feedback.

The third approach (Underhill, 1991 as cited in Asif & Jabreel, 2014, p. 153) is geared towards individual teacher development within an established group of people working together and “is likely to create interpersonal, caring environment with a shared commitment to the process of intentional development” (Asif & Jabreel, 2014, p. 153).

The fourth approach was introduced by Borg (1998) and its target is to use classroom data to acquire new skills. The term data is characterized as “the description of ELT lessons and interviews” (Asif & Jabreel, 2014, p. 153) in which teachers discuss their work.

Concluding remarks

It could be argued that implementing a teacher development program may be challenging since it entails the notion of change which “is a process of interaction, dialogue, feedback, modifying objectives, recycling ideas and coping with mixed feelings and values” and may trigger “feelings of threat, insecurity or concern about personal exposures” (Asif & Jabreel, 2014, p. 157). Nevertheless, teachers who are engaged in the process of professional development may also have the ability to adopt “principled eclecticism” (Richards & Rodgers, 2014, p. 352), namely the blending of different teaching methods into their own personal method and find the best balance in language teaching. •