Part 3 of this series of articles on story telling will start by suggesting that stories be implemented more frequently in the English classroom since they are powerful tools and involve children in an enjoyable way in the learning process. Story telling is mostly associated with young learners, but I propose a broad use of this tool involving all ages. The idea is to urge students to read, listen to, tell, act and devise stories. Our initial aim in the story telling project in education is to get students to “tell” or “act out” a story; then to devising their own story.

By Zafi Mandali, Director of the Departmentof Englishof Ellinogermaniki Agogi

The story telling activity is introduced with the teacher telling or reading a story and so serving as a model for this activity. Not only listening activity is provided in this way, but also students’ attention is drawn into story reading and telling habits. The teacher builds up a collection of short but memorable stories which is given out to students as reading material. The students then chose the story to do and decide if they will do it on their own or in a group. If they take the group option they decide who will be in the group and assign roles within the group. Then they will have to agree on props, music and any digital support -a power point for instance-, to accompany their telling. The presentation is to be given in class or at a story telling event which the teacher will organize. In the previous article I focused on developing students’ awareness of the universal story structure, functions and elements. This knowledge will help in the story presentation and facilitate the story devising step which we will take in this article. It will also come handy in the next step of the story telling project which is digital storytelling, to be elaborated in the next article.

“Once upon a time, in a far, far land…” are words which magically draw us into the story web and into worlds where the rules of logic do not apply and anything is possible. The definition of storytelling according to The National Storytelling Association is “The art of using language, vocalization and physical movement and gesture to reveal the elements and images of a story to a specific, live audience”. Now, how we do this is another story. How does the telling sound real, genuine and compelling and how do the story characters become relevant and appropriate for each specific audience? I want to say that “how” something is said is sometimes more powerful than “what’ is said.

To get help on “the how to tell” issue, we should think of how we tell a personal story. Telling a personal story is easier than telling a story we have recited because we tell it in our natural storytelling style, our own words and oral strengths, our own rhythms. The telling has become an automatic or subconscious process. When we tell a memorized story, however, and put all our energy into remembering and repeating a string of words instead of relying on the sensory details and feelings of these words, we are not doing things right. We should not act and adjust “us” to the story or do things in ways that are not natural for us. Instead, we should reform mental images into words when telling and this brings us closer to our personal, natural, day-to-day storytelling style.

{loadmodule mod_random_image,call to action subscribe in articles}

QUESTIONS TO ASK WHEN WORKING ON A STORY

“When children read for pleasure, they acquire involuntary and without conscious effort, nearly all of the language skills many people are so concerned about. When we read, we really have no choice – we must develop literacy”, Stephen Krashen, linguist and educational researcher. It is reassuring to know that Krashen’s long standing research gives academic alibi to what we always knew. And we have more reason to turn to graded readers, stories in coursebooks or e books or audio books. Especially now with Whisper sync technology when we can synchronize audio and text versions or switch between the audio and the book or listen while the words are highlighted along the way (look at Black Cat story books). Finding material is not the problem anymore. It is navigating the maze of material out there which is the issue.

Another issue is how to use the story as a springboard for motivating, engaging and memorable higher order questions. Stories give us a platform for questions. It is up to us to use questions which lead to creative thinking. With young kids we use stereotypical response question patterns of limited value. e.g.

- What color are lemons?

S: Lemons are yellow.

T: Yes, very good.

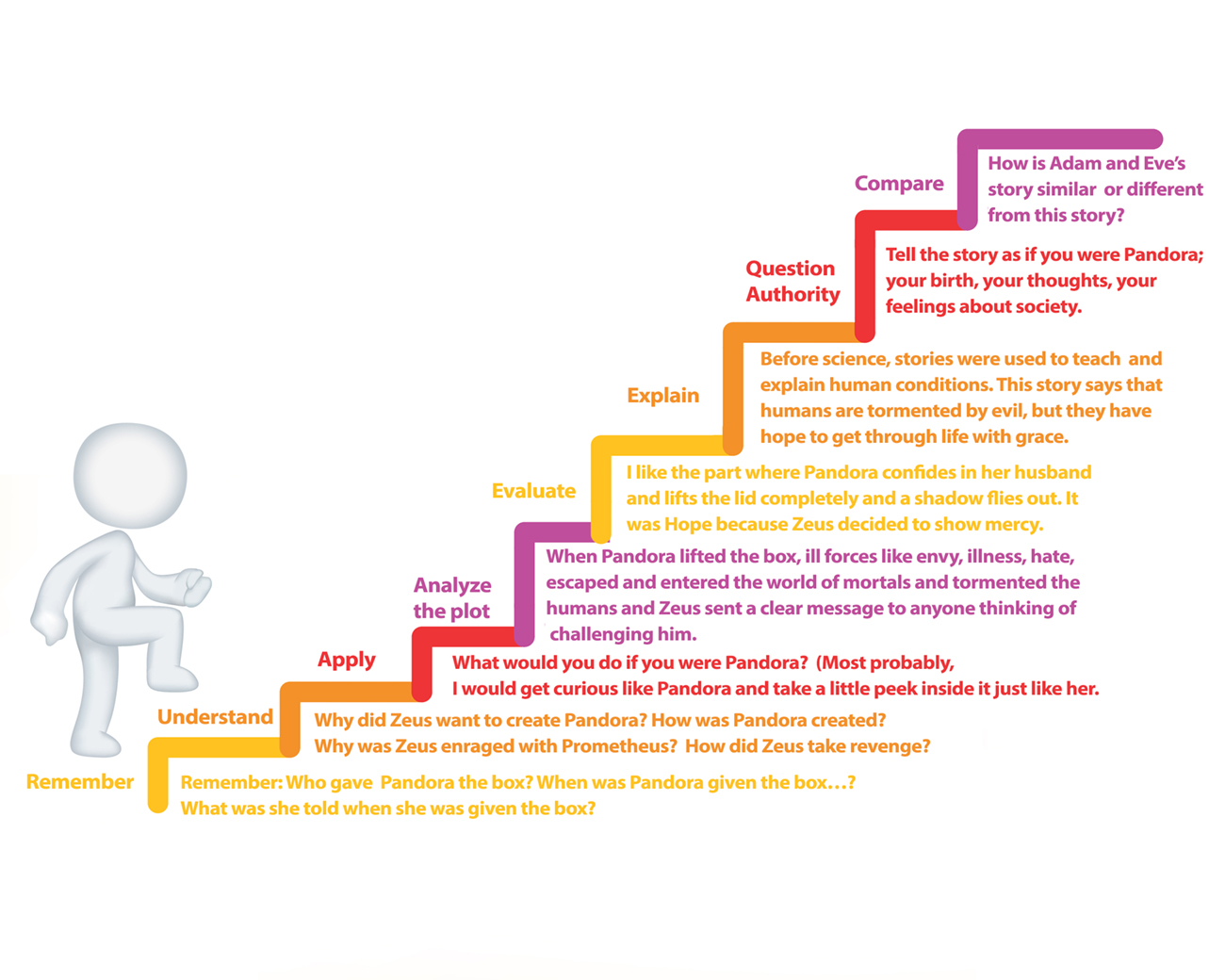

Such questions give us class participation but neglect deep thinking processes. So, when working on a story we do not only ask simple comprehension questions, which require recall and have a correct answer. We should ask challenging questions which interest children, help them open up and extend their thinking. Let us look at Bloom’s revised taxonomy of thinking skills (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001) to remind us of:

- a) the lower order thinking skills (LOTS) -remembering, understanding and applying-, in other words recall, identification and basic comprehension and

- b) higher order thinking skills (HOTS) - analyzing, evaluating and creating- which require complex cognitive effort.

Any questions which involve evaluating, imagining, and predicting require deep thinking. When we ask students to distinguish between fact and opinion, we develop critical thinking. When we adjust the story to create versions of it, we encourage divergent and creative thinking. Let us encourage students to be a little bit like Alice in Wonderland. When she descends into the rabbit hole, she proves herself to be a true critical thinker who questions everything she thought she knew.

Below, I am using the story of “The Pandora’s box”, an ancient Greek myth, to demonstrate some Low order and some Higher Order questions in accordance to Bloom’s revised taxonomy. Of course, what questions a teacher creates spring from the traces the story has left with him/her.

According to Greek mythology, Pandora was the very first mortal woman who appeared on earth. At the time, there were many Goddesses but not any mortal women around and Zeus asked Prometheus, the Titan, to provide him with a mortal daughter. Prometheus, who was busy at the time creating men for the earth, did not find the time for this. So, angry Zeus went to Hephaestus, the God of blacksmiths and fire and he created a woman from clay for Zeus. Then Goddess Athena, breathed life into the statue and other Gods and Goddesses gave Pandora traits such as beauty, charm and curiosity. It so happened that at the time Prometheus stole fire and gave it to men so that they would stay warm and cook; this enraged Zeus because at the time it was only Gods who used fire. So, Zeus worked up a revenge plan. He gave Pandora as wife to Epimetheus, another Titan, who was Prometheus’s brother. Zeus had an ulterior motive for this. He gave Pandora a wedding present, a beautiful box with a warning not to open it unless she was told to do so by the Gods. Pandora could not resist her curiosity, opened the lid and terrible things got out to torment the human race. Zeus got his revenge on Prometheus but also sent hope to the human race to remedy things.

Low and high Order thinking Questions

A BRIEF TUTORIAL ON STORY DEVISING

How do you devise a story if you are a 14-year-old? The good news is that teenagers have active imagination. The bad news is that they are impatient to get down to the technicalities of the matter. So, we tell them that writing a story is like creeping into a forbidden house. The story starts with something ordinary, then something mysterious happens and gets your hero into trouble. Normal life is suspended, and the main character is presented with a problem to solve, an obstacle to overcome, a mission to accomplish, an opportunity or a goal to address. Adventure begins, tension is created, the mood is set for the story reader to know how the challenge will be resolved. A story needs a mystery, a time bomb to keep the reader alert. In the Frog Princess story, the promise the princess makes to the frog so that it gets her the ball from the well, explodes when the frog comes into her bed. Also, students must be reminded that a moral choice must be brought in their story. Will the princess allow the frog to sleep with her? To make things even better one can have the hero make a seemingly wrong choice like in Jack and the Beanstalk who sells his cow for some beans. His mum gets furious; in her opinion Jack made a terribly wrong choice. As he climbs the beanstalk a thrilling expectation builds especially when we read :“Fe, fi, fo, fum! I smell the blood of an Englishman. Be he alive or be he dead, I’ll grind his bones to make my bread”.

What follows is an overview of the most common assistive techniques to approach story writing. I start from the simplest and move on to the most complex ones, leaving the choice to the reader.

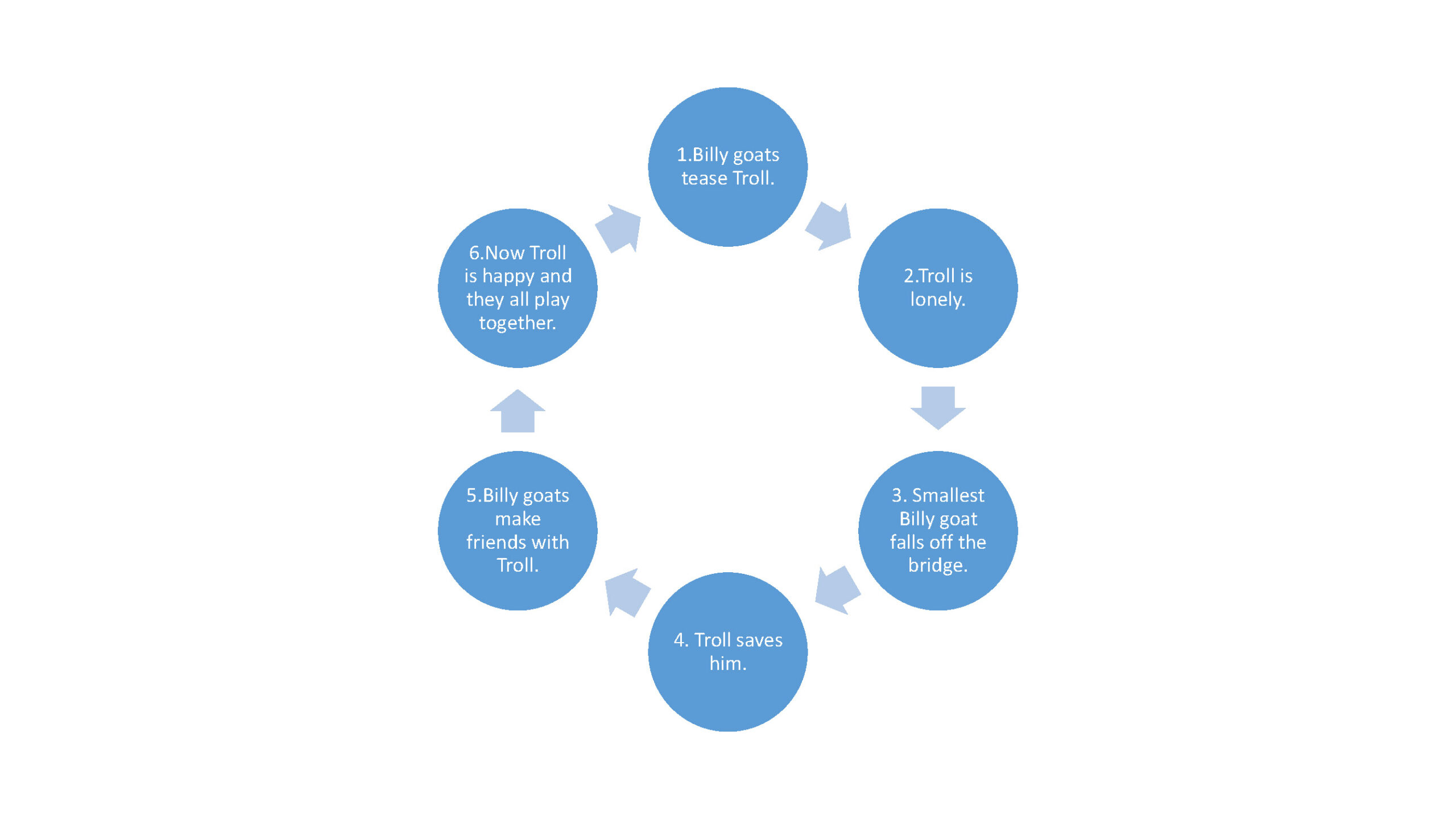

- a story list (the student writes the order of things happening in a supermarket list fashion)

- a story web (where the order of evens is presented in circular fashion)

- a story mountain (on a mountain outline the student jots the events starting from the base, moving upward to reach the summit where the climax of the story happens and then descending back to the base as the resolution unfolds).

- a story map or a story template, a one-page story skeleton, on which I will expand in the next article.

- The story board, essential in digital storytelling, which will also be illustrated in the next article.

List Sample Spider Diagram Sample

If students complain of having no ideas (the writer’s block), we can suggest that they create a version of a well-known story which they have enjoyed and imitate it, changing the setting, the characters and events. The story could be anything from what they had heard or read and had enjoyed.

With this technique, the students have the story elements and they only need to give them a new context.

Further Reading

Drama Techniques. Alan Maley and Alan Duff, third edition, Cambridge.

http://www.magickeys.com/books/http://www.starfall.com/

The Science Behind Storytelling – and Why it Matters by Gavin MacHahon, SlideShare Blog

Zafi Mandali. Director of the Department of English, Ellinogermaniki Agogi. She holds a BA in English Language and Literature, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and an M.A. in Applied Linguistics, University of Essex. Her soft point is Storytelling which she has been practicing with her team.