For those of us who embarked on the adventure of learning English during the 80s we cannot help but remember with a big dose of nostalgia the adventures of Arthur Newton a shy, penniless, young librarian who goes back to college and wins the heart and hand of Mary, a pretty fellow librarian. It was a time that language schools (and video clubs!) popped like mushrooms in every corner of every neighbourhood all over Greece. We were learning English with a course book that defined an entire generation and exposed us to the English language and the British culture.

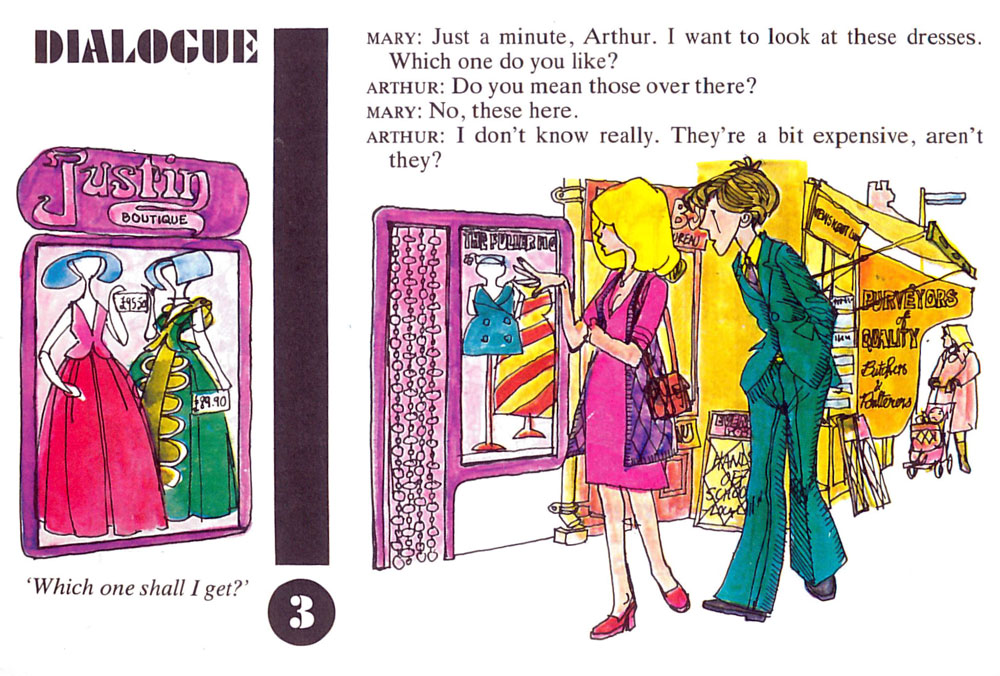

Arthur Newton, Mary Stephens and Bruce Fanshawe were the three main characters of the Access to English series by Oxford University Press (Written by Michael Coles and Basil Lord and designed & illustrated by Peter Edwards.). The series included four parts (Starting Out, Getting On, Turning Point and Open Road), starting from A class all the way to FCE. It was a course book filled with interesting stories, pictures and illustrations.

As a student I loved it because the story was funny and the texts were humorous. I could step in to Arthur’s shoes and relate to his struggles to impress Mary, just as I was trying to impress the girl I had a crush on in second or third grade. I remember wanting to do the homework so we can get on with the next chapter in order to see what will happen next. The Access to English episodes often employed effective devices and techniques borrowed from literature. For instance, the passages in the chapters often end in suspense. It was like a TV series like “Friends” or “How I met your Mother”.

Even though Arthur was an Englishman (no relation to Sting!) in 1970s Britain, his story could be understood by anyone. No previous knowledge of the era or the place was necessary in order to be able to relate to Arthur’s ‘light-hearted adventures’. Such an approach to culture put non-native speakers on the same page as native speakers.

Teachers adored it as well. The quality of its texts and the way it engaged students made the classroom a fun place to be. In Access to English, text played a central role: each unit begun with a narrative and a related dialogue, which provided the thematic context for the exercises and drills that followed. In fact, the books offered a commodity that was scarce in ELT those days: an excellent storyline made up of a string of well written, engaging texts. (Illes, 2009).

The texts in Access to English could be used for a variety of purposes, including discussion, storytelling, role play, or the explicit teaching of productive vocabulary. The chapters had the amount of new lexis that could be realistically taught and tested. Teachers could easily set aside five minutes of each lesson to ask one to two learners to summarise or act out an episode, and give marks for their performance.

Access to English had the ingredients ELT course books often lack: interesting and motivating topic content, the use of fiction, appropriately sized, coherent, and engaging (reading) texts which stimulated the imagination of learners (Tomlinson, 2001). The unprecedented success of Access to English suggests that there is demand for such well-written pieces, and that texts bearing a close resemblance to works of art may be highly beneficial, if not essential, for stimulating and pedagogically effective materials.

It then appears that authors who know how to tell a good story (for example, J. K. Rowling, who, in fact, taught English in Portugal at one stage of her life (http://www.jkrowling.com)) and ELT Experts who could add the necessary pedagogic components would make up the ‘dream team’ of course book writers. (Illes, 2009).

All ELT course books are designed to teach English; in addition they carry cultural messages and have pedagogic and commercial purposes.

Why do most course books resemble each other nowadays? According to Gray, J. (2002), iIt’s because most ELT publishers provide the course book writers with approximately the same set of guidelines for writing the content of the course books. These guidelines include two areas: inclusivity and inappropriacy.

Inclusivity deals with a non-sexist representation of women in course books. Inappropriacy deals with the avoidance of subjects that could offend buyers and readers and thus affect purchasing of the texts. Contemporary course books then can be regarded as ‘feminized’ for ethical reasons, and ‘sanitized’ for commercial aims.•

Words: Dimitris Spyropoulos | dimitris@eltnews.gr

Illustrations: Courtesy of OUP