“The greatest discovery of my generation is that human beings can alter their lives by altering their attitudes of mind” (Williams James, 1842-1910)

The Appetizers

In educational psychology, Academic Self-Concept (ASC) refers to students' self-perception in specific disciplines (e.g., math self-concept, science self-concept) or more general academic areas (i.e., global/general ASC) (Marsh et al, 2008). As a prominent construct in educational psychology, student ASC showed substantial positive relations with many desirable educational outcomes, such as academic effort , academic interest and long-term educational attainment. Earlier empirical research and a meta-analysis manifested that academic achievement and ASC are reciprocally related. Positive ASC is an important means of facilitating student academic accomplishments and has been regarded as one of the key objectives of education; therefore delving into the ASC forming process and revealing the forming mechanism make an impact both academically and practically.

The Big Fish Little Pond Effect (BFLPE) is one of the most influential theories about student ASC forming process, which was proposed by Marsh (1984) to describe the phenomenon that students in selective schools always have lower ASC compared to those with comparable ability but attend regular schools, which means that being a big fish in a small pond does good to one's ASC. Considerable evidence substantiated that the BFLPE is thought to be the outcome of individuals comparing their ability with the average ability of their group.

It has been demonstrated that student's ASC is shaped not only by his or her performance but also by social comparisons. Students compare their own achievement with that of their class- or schoolmates, which leads them to feel more negative about their own competencies in high-achieving atmosphere than in low-achieving atmosphere. Marsh argued that this social comparison mechanism lies at the heart of the BFLPE.

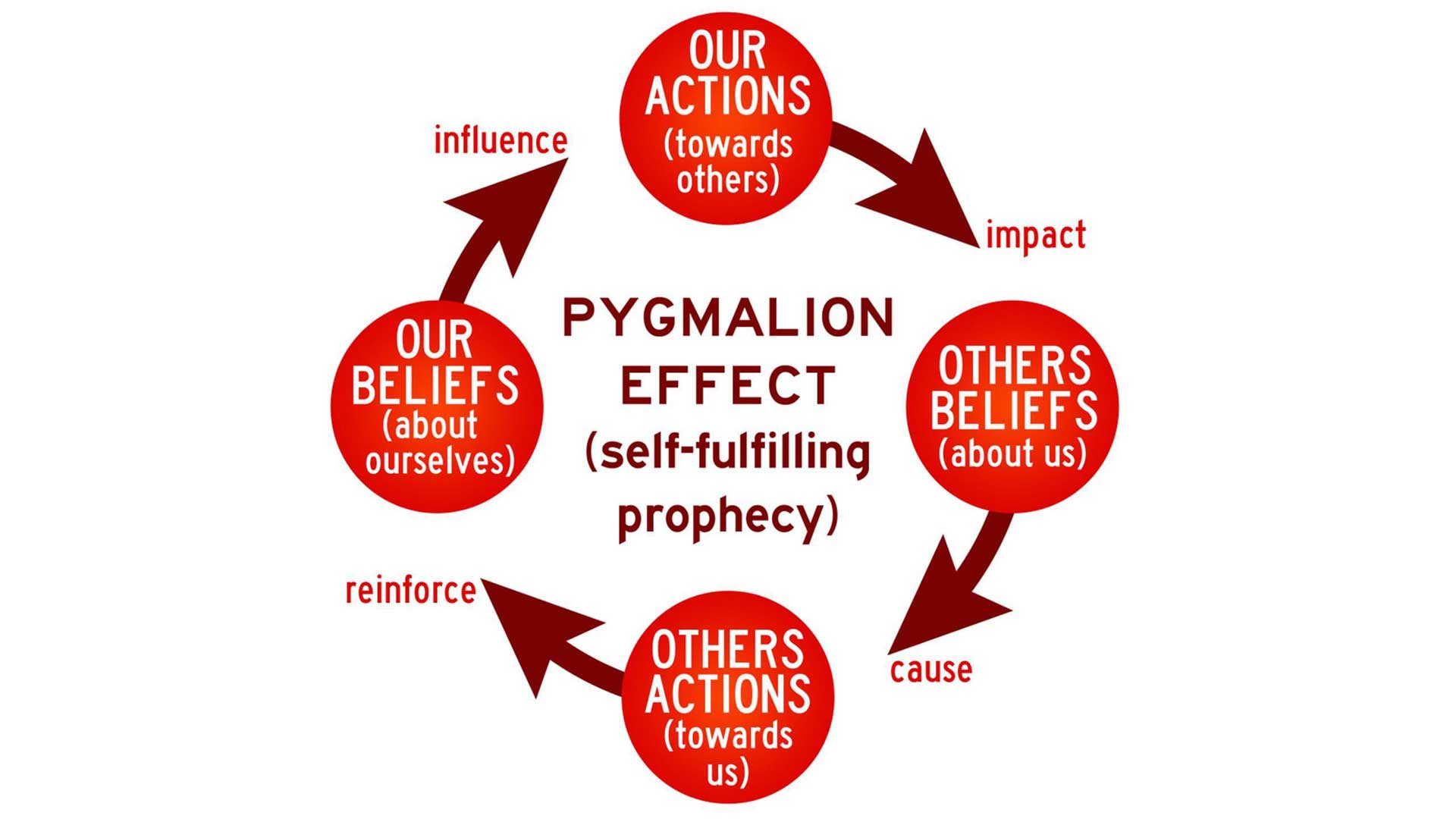

Pygmalion first appeared in Greek mythology as a king of Cyprus who carved and then fell in love with a statue of a woman, which Aphrodite brought to life as Galatea. Much later, George Barnard Shaw wrote a play, entitled Pygmalion, about Lisa Doolittle, the cockney flower girl whom Henry Higgins, the gentleman turns bets he can turn into a lady.

Nowadays, the “Pygmalion effect” usually refers to the fact that people, often children ,students or employees, turn to live up to what’s expected of them and they tend to do better when treated as if they are capable of success.

In the teaching and researching domain, the “Pygmalion effect” was also called “Rosenthal effect” because of the classic experiment by Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968; summarized by Pintrich and Schunk, 1996).

At the beginning of the academic year, Rosenthal and Jacobson told the teachers that this test was to predict which students would “bloom” intellectually during the academic year. They deceived the teachers that their genius students had been tested by some new methodology of determining the success of school age children, and these kids were the best of the best.

In fact, the students were randomly chosen from 18 classrooms and their true test scores would not support them as “intellectual bloomers”. The result of the experiment showed a distinguish difference between the sample students and the control students. The “bloomers” gained an average of two IQ points in verbal ability, seven points in reasoning and four points in overall IQ. The experiment showed that teacher expectations worked as a self-fulfilling prophecy. If teachers were led to expect enhanced performance from some children, then the children did indeed show that enhancement.

The Main course

The question then seems to be to what extent and how a teacher may shape student’s performance in a way that he or she would activate his/her inner incentives and manage to outperform himself/herself and satisfy this teacher’s expectations.

The answer to this question is through positive encouragement and praise. Teachers need to give feedback in class about language and errors. But they also need to provide feedback on more personal things, such as achievement, behaviour, motivation, participation, attitude and so on. Which is the best way to do so? Through praise or positive encouragement? Most teachers would respond both. But if we look a little bit more carefully into the effects of praise, the right answer will be: positive encouragement. To help you ponder on that, I will ask you to compare the two strategies.

|

Praise |

Supportive Feedback |

|

Evaluates the person and the work |

Evaluates the work |

|

Tends to be generalized, does not exemplify |

Tends to be specific, uses concrete examples |

|

Comments are stated as if they are some objective, universal truth |

Comments are often owned by the comment maker |

|

Notices tasks completed well, does not typically notice engagement and effort |

Notices work at all stages, acknowledges engagement and effort |

|

Compares a student’s work with others in the class, it draws attention to achievement of the best class members |

Compares a student’s work with their own previous work, it draws attention to achievement and progress for that individual student |

|

Does not give information about how to improve |

Gives useful information about how to improve |

|

Encourages truths in the teacher’s assessment |

Encourages self-assessment |

|

Mostly reserved for the best, fastest, cleverest, etc. |

Available for all students of all abilities |

|

Becomes a bit meaningless over time, as there is nowhere else to go after ‘fantastic’ |

Keeps its value over time as it addresses new issues |

|

Always good news |

Can be bad news given in a supportive way, as well as good news |

|

May come across as a habitual or token comment |

Sounds as if it springs from a genuine positive reaction |

|

May present a simplification or glossier version of the truth |

Tells the truth |

(Classroom Management Techniques, Scrivener Jim, CUP, 2014, pp 164-165)

The Fortune Cookie

The main purpose of our teaching should be learners to become independent and autonomous language users and human beings. Praising may help learners build their self-image and their self-confidence but it is for short time. Positive encouragement (supportive feedback) is an alternative, more long-term and effective way learners to develop a healthy, organic reflection on their responsibilities for their own learning, progress and performance.

It will also be worthwhile to introduce alternative ways of supportive feedback. Try using “learning diaries” where learners can record their own progress in their own words. If they are new to the language, ask them to use their mother tongue to describe both their weaknesses and their strengths.

Another suggestion would be self-assessment in the form of “can-do-statements” where students record only their achievements using again their own words, reflecting on their progress, monitoring their own learning (great meta-cognitive task).

Above all, reconsider the way you give feedback in the classroom.