Pronunciation can be a challenging and intricate aspect of language. It involves the correct articulation and vocalization of sounds, intonation patterns, stress placement, and rhythm. Pronunciation varies greatly across languages and even within different regions or dialects of the same language.

For learners of a new language, mastering pronunciation can be particularly difficult, as it requires understanding and reproducing unfamiliar sounds and patterns. Many factors contribute to the complexity of pronunciation, including phonetics (the study of speech sounds), phonology (the study of how sounds function within a language), and phonotactics (the rules governing sound combinations).

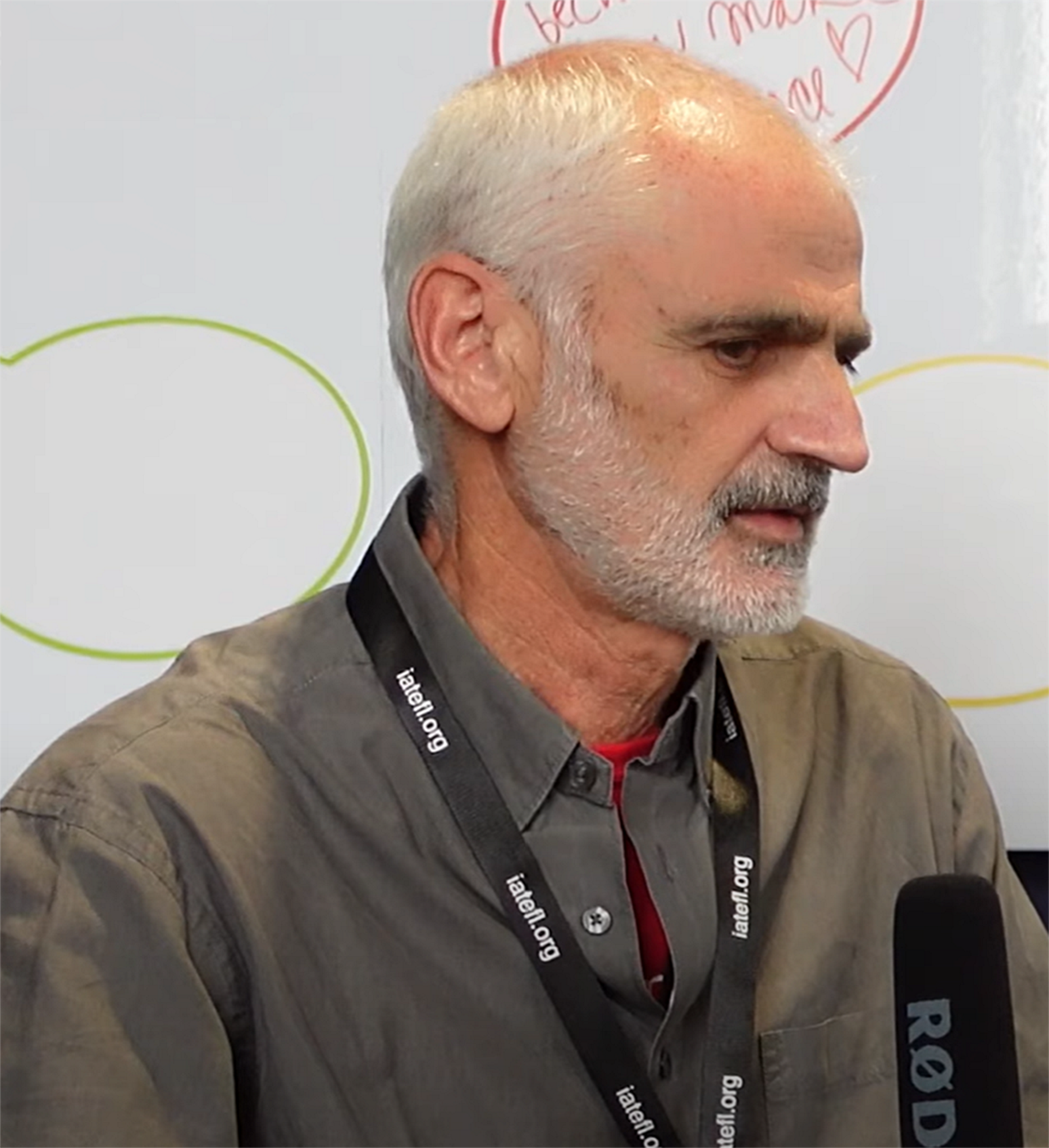

Robin Walker has worked in English Language Teaching since 1981. He now works as a freelance teacher, teacher educator, ELT author, and ELT consultant, and regularly collaborates with teacher training centres around Spain, with Oxford University Press, Oxford University Press España, Trinity College London, and Servicios y Gestión Educativa. His main interests are pronunciation, teacher education, and English for Specific Purposes (ESP).

Teaching the pronunciation of the English language can be a challenging task, especially for non-native speakers. Where should we start? From individual and vowel sounds and diphthongs?

When I started studying the subject of phonology and phonetics at the university here in Asturias where I live, we began with the consonants, then went on to vowels, then word stress, and finally rhythm. We never made it to sentence stress, intonation or connected speech as we ran out of time. We must have been an especially bad group to have taken so long to get only two-thirds of the way through the syllabus. There was a logic to starting like this for a university course in phonetics, but that logic doesn’t apply to teaching pronunciation in schools, or later with adults needing to communicate in English.

Personally, I wouldn’t start with individual sounds. Beginners need to speak, and that means getting words out of their mouths. So, at first, I’d want them to work on pronouncing whole words, mostly by imitating me or the coursebook’s recorded model pronunciation. From there, I would quickly move on to short phrases or simple sentences, and at this stage I’d be very tolerant of what my students were able to pronounce, especially with respect to the vowels, which are such a nightmare for so many learners.

If you go about early pronunciation work in this way, then inevitably your students’ attempts to pronounce certain words or phrases throw up bits of some words that they just don’t seem to be able to articulate comfortably. Then, and only then, would I drop down to the level of individual sounds, but even with these problems sounds I’d be very relaxed about what constitutes good enough pronunciation. Perfection can wait for later. A lot later. In that respect, Judy Gilbert has hugely influenced me. Her approach has always been to get pronunciation to serve the needs of the message, and she has always essentially gone down from the top, down from the suprasegmental ultimately reach problematic individual sounds. David Brazil did the same in his course book based on his discourse approach to intonation.

Text by: Anastasia Spyropoulou

Is it useful to introduce phonetic symbols? Don’t we run the risk of confusing our students when we do so?

There was a time back in the 1980s when ELT seemed to get so excited about IPA symbols. As a result, they started appearing everywhere, especially in coursebooks. And yes, they can be useful to break the tendency that many students naturally have to pronounce every letter in the written form of a word as an individual sound. My students are Spanish-L1 speakers of English, and so left unchecked produce ‘are’ as [ˈare] as opposed to /ɑː/. Telling them to look up the pronunciation of a word via the IPA symbols in the dictionary at least forces them re-think what that word should sound like. But in many cases, things didn’t go much beyond re-thinking. For production there is a hidden problem with IPA, which is that very few students actually have a sound in their heads that corresponds to a given symbol. So, going back to my Spanish-L1 students, most often the IPA symbols as in /ɑː/ told them NOT to pronounce [ˈare], but didn’t actually help them get to the right pronunciation.

Later in my career, as I travelled around giving talks and workshops, I also came to realise that the IPA symbols were an added burden for what was already a major problem for learners coming to English from non-alphabetic languages such as Chinese, Japanese or Arabic. These learners surely have enough on their hands with learning to write using the alphabet without having to take on the additional system of IPA, which (sadly) coincides too often with alphabet letters. In the end, regular contact with primary school teachers made me think that rather than introducing IPA, it would be far more productive to adapt a phonics approach to the teaching of the pronunciation of English. I’m not saying that IPA doesn’t have its uses, but I can see myself moving towards a moment in which I’ll barely use it in class myself.

Most online dictionaries have a sound bite. We can hear how a word is pronounced as many times as we wish. Isn’t it a better way for our students to learn how to pronounce a word correctly?

A sound bite is another tool in our armoury. It can be really useful, but it is not a miracle cure. If your first language does not distinguish between /s/ and /ʃ/, for example, then you aren’t going to make the distinction in your own pronunciation just because you heard a sound bite. Quite early on in life, we lose the ability to distinguish between sounds that have no phonemic value in communication in our L1. Polish, for example, has six affricates compared to only two in English. A few years ago in Warsaw, despite careful modelling by a Polish friend and pronunciation expert, I failed miserably to hear the six separate Polish sounds. So, going back to /s/ and /ʃ/, if you are learning English, but your mother tongue doesn’t distinguish between these two sounds, for example, then when you listen to the dictionary audio for ’sin’ and ’shin’ you will very probably hear the same thing. And if you hear the same for both sounds, you will then go on to pronounce the same thing for both words. Dictionaries with audio are a definite improvement on purely paper dictionaries, undoubtedly, but learners will still almost always need the help and guidance of a trained English language teacher to get the best from the dictionary’s sound element.

How can we teach intonation and stress?

We can start by clarifying in our own mind what we mean by these two terms. They are frequently used as if they were separate concepts, when in fact there is significant overlap between them. Stress, for example, can be lexical stress, which we more often refer to as word stress. But it can also be sentence stress, which is more correctly referred to as tonic stress or nuclear stress. Word stress is a fixed property of a word as is shown in our dictionaries and is relatively simple to present and explain to students, although that in itself does not guarantee that learning will follow. I had a private student for a number of years who was a bio-organic chemist. The word ‘enzyme’ was key to his work, but after countless attempts at getting him to put the stress on the first syllable, I gave up. It was obvious that it was never going to happen.

Sentence stress is quite a different beast to word stress. Any word in a piece of spoken English – in an ‘utterance’ – can be stressed. But in the basic unit of spoken English (often referred to as the tone unit), one word is more stressed than the others. For example, in ‘Can I help you?’, the word ‘help’ is the most stressed. This is the nuclear stress (or tonic stress), and it is at this point in an utterance that the voice changes pitch, going up or down, or down then up, to create what we call the tone. The tones in English can be level, fall, rise, fall-rise or rise-fall, and they can be from a high, mid or low pitch. This is all beginning to get quite complicated, but this is only just the beginning. The rest of the intonation is far more complicated.

So, how can we teach intonation and stress? Interestingly, there are some things in life that don’t respond that well to classroom teaching and are best left to be acquired in the real world through meaningful use. Using intonation to express attitudes like boredom or unhappiness is one of these things, and I stopped trying to teach this to my students many years ago. I later came across a comment by Peter Roach, who at the time was Professor of Phonetics at Reading University, that confirmed my decision to not teach them to use intonation to express attitude. He said ’The attitudinal use of intonation is something that is best acquired through talking and listening to English speakers’. In other words, this aspect of intonation is ‘learnable’ but not ‘teachable’, and so we shouldn’t waste our time on it in the classroom.

But that isn’t to say none of intonation can be taught in the classroom, and in that sense, I concentrate my own classroom practice to work on tonic or nuclear stress. So, while I’m not too worried about the exact tone they use when they ask ‘What time is it?’, for example, I am worried about them putting the tonic in the right place, which is on the word ‘time’, and I focus on this in class. Getting students to detect the tonic syllable in an utterance is not that difficult, and getting them to produce it correctly is also well within their grasp, though not as easy. What is far more difficult in my experience is getting them to use the right tone, and so I no longer bother to try, as I explained earlier.

Is the teaching of pronunciation neglected in the ELT classroom as time-consuming?

I wouldn’t say neglected, but it does tend to get squeezed into a corner when time is short. Interestingly, my students once admitted to me that while they appreciated my efforts to help them with their pronunciation, they themselves didn’t spend any time on it outside the classroom because it wasn’t in the course evaluation. Students are under so much pressure now that I had to accept what they had confessed to me and feel grateful for their honesty. And I was genuinely grateful because their comment was a wake-up call. If I wanted my students to take pronunciation seriously, I had to start giving it a mark. A couple of years after this comment I had engineered a system through which my students handed in recordings of work I set them, so that I could check these and give them a mark for their pronunciation. Once I started doing this, the change in their attitude towards pronunciation was total. Real night and day stuff. In fact, whereas I would typically get about 70–80% of my students handing in written assignments on time, I almost always got close to 100% of the pronunciation assignments in or before the deadline. And surveys that I did showed that my students really valued pronunciation now.

Is there a definitive Standard English pronunciation?

No, there isn't. I accept that like so many of us I am as guilty of using the term ‘standard’ when referring to pronunciation. But some time ago, I was reading an article by Peter Trudgill, the British sociolinguist, and he explained that although Standard English exists, it can be spoken with multiple different accents.

It is more correct then, to talk about a prestige accent, which is one that has been designated as being the reference accent for a language in a given country, although that designation is never taken on phonetic grounds, but on the basis of socio-political considerations. Then of course, comes the question of whose ‘Standard English pronunciation’. The prestige accent for British English, Received Pronunciation (RP), is hugely different from General American (GA), the US prestige accent. And today, to these two we would have to add prestige Australian and New Zealand accents, and so on. It is true, then, that we often refer to a standard accent when we mean the language’s prestige accent, but it is impossible to name a single, definitive ‘standard’ English accent.

Has the use of English as a Lingua Franca had an impact on the pronunciation of the language?

Yes, a very significant impact. In fact, pronunciation is the area of English that has been most impacted by lingua franca use of English. And this is going to continue to happen more and more as L2-users of English communicate successfully with each other despite speaking with accents that don’t come even close to the model, native-speaker accents used in coursebooks. But the impact of English becoming a lingua franca is really surprising when you look at the ever-increasing amount of anecdotal evidence that strongly suggests that in ELF settings, the pronunciation of many native speakers is often the least intelligible of all of the different accents in the communication. Now that’s an impact! And in fact, the impact is so noticeable that there are now courses to help native speakers of English become more intelligible when English is being used as a lingua franca.

Has the use of English as a Lingua Franca led to the development of new accents and pronunciation patterns that reflect the diverse linguistic backgrounds of its users?

More than lead to the development of new accents and pronunciation patterns, I would say that ELF use of English has led to L2 accents being accepted as totally legitimate for international communication. Up to now, when learners have not achieved a native-speaker accent, there has been a general feeling of ‘unfinished work’. I remember during one of the recording sessions for Teaching the Pronunciation of English as a Lingua Franca I was suddenly faced with the problem of telling a German woman that I couldn’t use the recording she had made for me in my book because her pronunciation was so near-native. I was wondering how to tell her what seemed like it was going to be disappointing news when she asked to speak to me in private. She then told me that she wanted to withdraw from the project – she didn’t want people hearing her ‘terrible accent’. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Her accent was too near native to be of use to me, but she thought it was terrible. That is a dreadful indictment of the NS-accent system she had gone through, and if ELF use of English is producing any meaningful developments, I would say that it is in the increasingly wide acceptance of accent, whichever accent, provided the accent is intelligible.

Robin Walker will be a plenary speaker at the Thessaloniki Foreign Languages Forum held at Capsis Hotel on 26 August. He’ll also conduct a workshop in which he will:

- Determine teaching priorities – using the Lingua Franca Core he’ll ‘filter’ traditional lists of problems and produce a list of top priorities for Greek L1 learners aiming at international intelligibility.

- Provide some useful teaching techniques.

- Look whether the learner’s L1 is a resource or an obstacle to good pronunciation.

Please check out https://flforum.gr/the-cities/2023-autumn-thessaloniki-saturday-26-august and register for free.