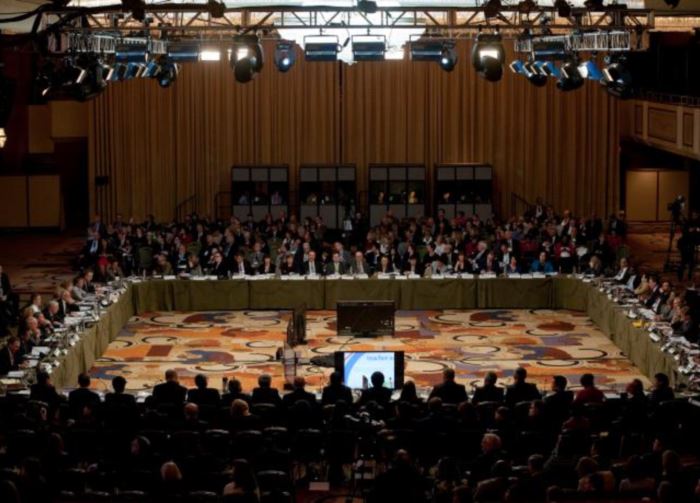

International Summit on the Teaching Profession

Each spring, education ministers, master teachers, national union leaders, and education organization leaders convene from countries with high performing and rapidly improving educational systems. The purpose of the gatherings is to identify best practices worldwide that strengthen the teaching profession and raise student achievement.

The first two summits in 2011 and 2012, held in the United States, developed a consensus that achieving a high-quality teaching profession is critical to education systems as they face the increasingly ambitious demands of the 21st century. Moreover, the highest performing countries are successful because they take a comprehensive approach to recruiting, preparing, supporting, and retaining talented teachers and school leaders.

The Summits spurred action on these issues in many of the participating countries over the past two years. The 2013 Summit, which was held in the Netherlands and hosted by the Dutch Ministry of Education, OECD, and Education International (the global federation of teachers’ unions), took on the complicated issue of teacher evaluation. This gathering of ministers of education and teacher union leaders, the 2013 International Summit on the Teaching Profession brought together delegations from the top 25 countries on OECD’s PISA assessment of student achievement as well as from several rapidly improving countries.

Why evaluate teachers? Education systems around the world are setting ambitious goals for both high performance and high equity. This requires high-quality teaching for each and every student. OECD surveys have shown that the vast majority of teachers (83%) welcome informed feedback on their teaching as a way for them to improve their teaching and felt that the feedback they had received had been fair. However, in the countries surveyed, more than one in five teachers report never receiving any feedback from their principal or a senior teacher; others report that there is no recognition for superior performance; and in some places, 95% of teachers receive satisfactory ratings even where student achievement is weak.

So teacher appraisal systems are seen as a potentially powerful engine for improving teaching and offering new roles for outstanding teachers and are the subject of increasing attention around the world. Despite the often-contentious nature of discussions of teacher evaluation, there are, in fact, broad areas of agreement between governments and teachers organizations. Most countries do have teacher standards that define teaching quality. They also have appraisal systems although these vary enormously in design -ranging from informal conversations between principals and teachers in Finland, to peer review systems as in the Netherlands, to highly developed annual performance management systems like in Singapore.

The definition of the role of the teacher, the education governance structure of the country, the existence of career ladders or not, and the styles of evaluation in other careers in the country all influence the design of teacher appraisal systems in different contexts, so there is no single universal approach.

The definition of the role of the teacher, the education governance structure of the country, the existence of career ladders or not, and the styles of evaluation in other careers in the country all influence the design of teacher appraisal systems in different contexts, so there is no single universal approach.

But there is general agreement that to be meaningful, appraisals have to be in the context of professional development since research shows that feedback on its own, without opportunities for coaching and practice of new skills, does not reliably lead to improvement.

They also need to use multiple sources and measures of feedback (many countries include parent and student surveys as well as classroom observations, self, peer and principal assessment, and student test scores) to truly do justice to the complexity of the teacher’s role.

And they have to be designed in partnership with the teaching profession. Teacher appraisal systems also require significant attention to implementation. It is critical that there is good training for the appraisers, whether principals, senior teachers, or external evaluators, so that the appraisals are clearly expert and credible. And doing serious appraisal requires time, as does the follow up professional development. How the assessment of individual teachers relates to the evaluation of schools and of broader education policies also needs careful thought since the conditions for effective teaching may vary a lot from school to school.

There are also areas of emphatic disagreement, including the weight given to narrow student test scores or value-added measures in teacher appraisals and the relationship of performance to rewards, especially bonuses or merit pay (as opposed to salary differentials that go with different career roles). It is also difficult to balance the goals of improvement and accountability. Poorly designed or top-down appraisal systems can unintentionally create a climate of fear and resistance among teachers and inhibit creativity.

The question facing most countries is not whether to have a teacher appraisal system but how to get it right. This is still work-in-progress. Despite strongly held views, there is little research as yet on what works or how expenditures on appraisal compare to other uses of funds to strengthen teacher quality. The Summit had serious, honest, and sometimes difficult conversations as leaders of governments and teachers organizations examined their differences and explored ways to resolve them. It did not provide definitive answers but experimentation around the world is helping to clarify the issues in this area and provide a broader set of options for countries to consider as they seek to provide a high-quality learning environment for every child.