We have initiated a column run by Robin Walker, teacher, teacher trainer and an expert in pronunciation. Robin maintained a blog (https://englishglobalcom.wordpress. com/) for many years and fed it regularly until his retirement. He graciously accepted to share his posts with ELT NEWS readers. Terminology is provided in alphabetical order. Enjoy reading!

I ended my first post on accent last month by raising the question as to which accent we should use for teaching the pronunciation of English, so I guess that now I have to offer you some sort of answer. Here goes.

Given the amount of prejudice surrounding accents in English, it would seem that our best option would be to get our students to aim for something neutral. This, at least, is what one participant seemed to be referring to in a survey done in Hong Kong in which she admitted that she would prefer to have a Canadian accent on the grounds that it was ‘neutral English – not too American or Aussie or British’ (Li 2009: 90).

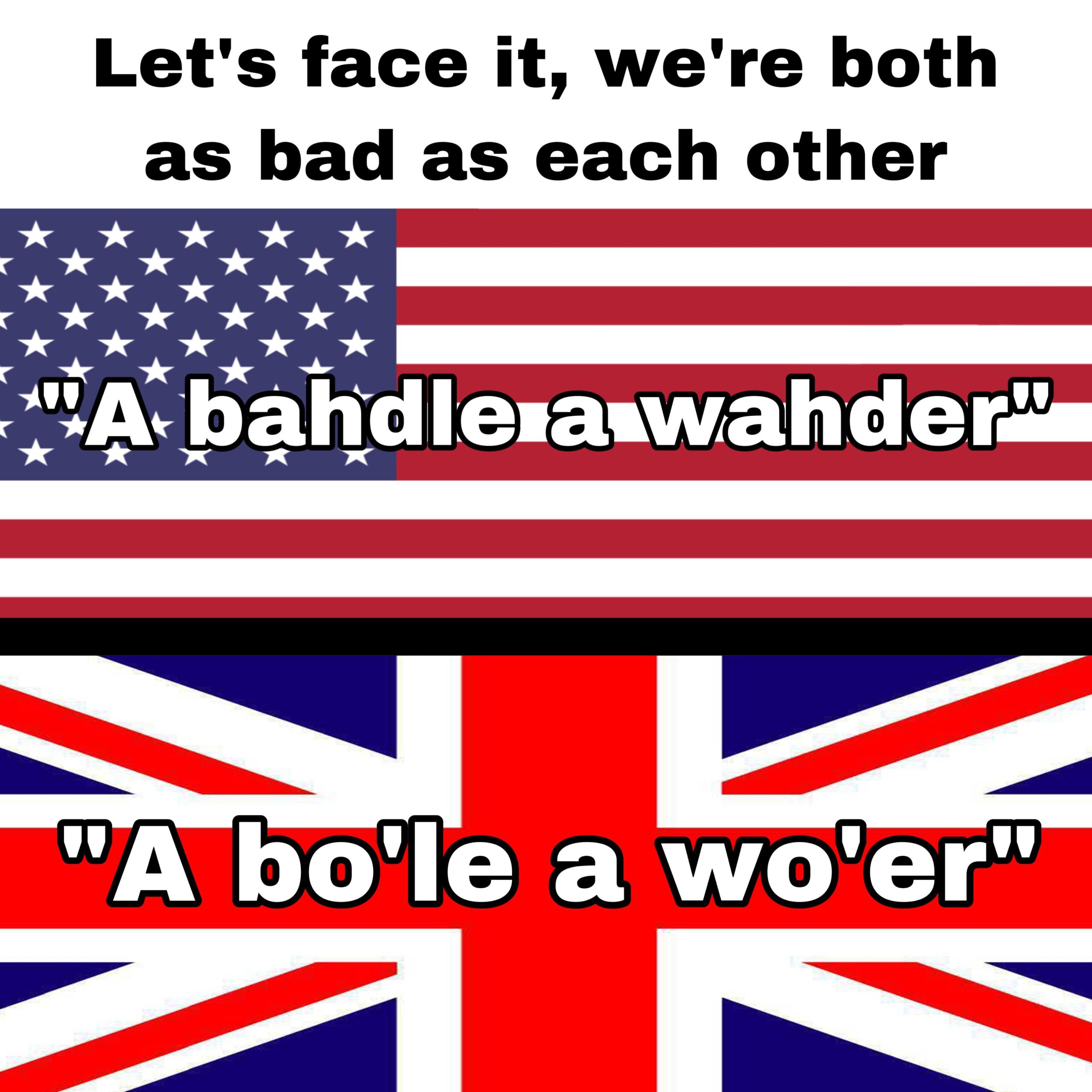

Unfortunately for our participant, there’s no such thing as a neutral accent. Accent is merely the difference between your pronunciation (or whatever you consider to be ‘correct’ pronunciation) and other speakers’ pronunciations, which to you, on being different, sound accented. I won’t ever forget the shock, for example, of my first trip abroad to another English-speaking country, to the US. I’m not going to say that I was put on bar stools in California and told to perform, but again and again my friend’s friends would comment on my ‘Briddish’ accent. ‘My accent’, I would say to myself. ‘You should hear yours!’

In the absence of neutral accents, then, perhaps what’s best for our learners is a standard accent. Surely people, or most people at least, will understand a standard accent. Good thinking, but, unfortunately, flawed. For the last few months, a colleague and pronunciation expert based in the UK has repeatedly rapped my knuckles for talking about ‘standard’ accents when, as sociolinguist Peter Trudgill tells us, technically there is no such thing:

Standard English has nothing to do with pronunciation. From a British perspective, we have to acknowledge that there is in Britain a high status and widely described accent known as Received Pronunciation (RP) … It is widely agreed, though, that while all RP speakers also speak Standard English, the reverse is not the case. (Trudgill, 1999: 118)

The correct term for accents like RP and the US equivalent GA (General American), is ‘prestige’. But leaving aside the constant references in the ELT literature to ‘standard accents’, let’s play the game, and in class stick to the prestige accents that are on the recordings for pronunciation exercises in coursebooks. Hey presto! Job done.

Save that it isn’t quite that simple. In a small-scale study carried out by the Academic Director of the British Council in Tokyo (Hemmi, 2010), the Japanese participants in the study (all employees at the Council in Tokyo) were asked to listen to recordings of five speakers from the international Davos Economic Forum conferences. Their task was to choose who they found the easiest to understand amongst these internationally skilled speakers, all of whom regularly communicated through English about complex economic issues.

Surprisingly (to me at least), the study found that the person deemed least intelligible was the only native speaker among the five. Receiving the accolade of being ‘easy to understand’ from only one out of the twelve participants, was the then UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, a prestige-accented speaker if ever there was one.

Hemmi’s study wasn’t the first one to reach the conclusion that native speakers, even with prestige accents, are not automatically easy to understand. A study carried out at the University of Hawaii tested the intelligibility of NS and NNS accents in English. The study concluded that ‘native speakers (from Britain and the US) were not found to be the most easily understood’ (Smith 1982: 88).

Choosing an accent for our learners to model, then, is not as easy as it seems. And a clue to why this might be so, comes from the work of Canadian researchers, Tracy Derwing and Murray Munro. Some time ago, their work led them to the robust finding that ‘accent and intelligibility are not the same thing. A speaker can have a very strong accent, yet be perfectly understood’ (Derwing & Munro, 2008: 2).

This separation of accent from intelligibility is one of the most important but least widely disseminated findings of research into pronunciation over the last twenty years or so. It’s important because it’s telling us as teachers, to shift our attention away from the fruitless search for the perfect accent to use in our classes as a model for our learners, and to place it much more firmly on helping our learners to improve in those aspects of their accents in English that could make them difficult to understand.

Accent has given way to intelligibility as the main focus of pronunciation teaching in the 21st century, and since intelligibility isn’t directly related to any particular accent, as the research of Derwing and Munro has shown, we can now get to the answer to the question with which I ended the previous post, and with which I started this one. The question about which accent to use in class when teaching pronunciation.

The answer, thankfully, is quite simple. Use whichever accent you wish, provided that:

- The accent you opt for is known to be widely intelligible to other users of English (native speaker and non-native speaker).

- The accent you choose is acceptable to your students.

- You have easy access to that accent for teaching purposes.

‘Whichever’, I hope you’ve already spotted, includes not just prestige accents like RP and GA, but also the regional accents of native-speaker teachers (sometimes referred to as ‘non-standard’), and the countless L2 accents of their non-native speaker colleagues. How many teachers have avoided teaching pronunciation in the past for fear of doing more harm than good with their non-standard/non-prestige/non-native speaker accents? Too many. Far too many. As the CoE points out, ‘the focus on accent and on accuracy instead of on intelligibility has been detrimental to the development of the teaching of pronunciation’, so as of now let’s start making up for the lost time.