What is dyslexia

What is my story (discovery, getting diagnosed, learning, studying)

What is my experience having it (feeling, stages to acceptance)

What is my experience teaching with dyslexia

When I was about eight or nine years old, I can remember my mom handing me the book during bedtime and asking me to read the story myself. I still recall how, no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t understand what I was reading. My mom, being the amazing educator she is, never let me feel like something was beyond my reach. She always encouraged me, always believed in me. But no matter how much I tried -or still try- reading has always been difficult for me.

My early school years didn’t help. In first and second grade, my teachers weren’t supportive. I was learning to write and spell noticeably slower than my classmates. They, not knowing any better, labelled me as “slow” and even called me “stupid” on occasion. The signs of dyslexia were there, but I was so argumentative and well-spoken that no one suspected it. Back then, “dyslexic” was just a fancy word for “slow” or “stupid.”

It wasn’t until third grade that my teacher suspected I might be dyslexic. She asked the special education teacher to test me. I vividly remember that test -I was determined not to “seem” dyslexic. I rehearsed responses in my head, asked other kids what they’d been asked, and planned everything. But the test wasn’t what it should’ve been. It felt more like a screening for autism than dyslexia. She asked me basic questions, my name, age, some details about school and friends. She showed me pictures and asked me to identify them. That was it. I wasn’t dyslexic, she concluded.

But my teacher didn’t give up. She saw how smart I was and made sure I saw it too. After two years of persistence, she convinced my parents to take me for a proper evaluation. My mom was worried that a label would follow me forever, while my dad -who didn’t see school as particularly important- had no idea how to help. They took me to a family friend, a Learning Disabilities specialist who taught university students how to diagnose dyslexia. So, my first official diagnosis was when I was 13 years old. I sat in a small room with a one-way mirror, behind which university students observed the process. The specialist tested everything: memory, writing, reading. She asked me about myself, school, and friends. She showed me pictures to memorize, asked me to copy sentences, and assessed my reading. I did it all wrong. Her conclusion? I had a normal to high IQ and was dyslexic.

I was a proud writer at the time, and finally, I had an answer. I knew why I loved books but hated reading. Why my stories were praised as creative but covered in red marks and low grades. Knowing I was dyslexic brought me a strange sense of relief – I was normal. I owe this peace to my mother, who always framed dyslexia as “learning differently.” She was right.

At 22, I now understand how much I owe to her belief in me. Dyslexia, to her, was never a limitation, and she made sure I felt the same. I felt compelled to prove everyone wrong -the teachers, parents, and classmates who equated dyslexia with stupidity. But most importantly, I wanted to prove my mom right: I am smart, I am strong, and dyslexia will never define my potential.

Dyslexia in the Classroom

As a novice teacher today, my heart breaks for dyslexic children who have already given up. They are bright, capable, and talented, but so many don’t see it. I have a student this year, a little girl at the A1 level. She’s sharp, a fast learner, and speaks with a beautiful accent. Yet, every time she makes a spelling mistake, she apologizes, even when encountering new vocabulary for the first time. She carries guilt for something as small as forgetting how to spell a word. Another student, a 12-year-old girl, has stopped trying altogether. She never does her homework, and I believe she’s afraid of making mistakes and being corrected. She’s already decided that trying is futile.

The sad truth is that many dyslexic children hear their first discouragements from the people closest to them. Parents, often out of ignorance, unintentionally reinforce the idea that their child is “less than.” When parents don’t know how to handle dyslexia, they ignore it, sweep it under the rug, or explain away struggles with, “You can’t do this because you’re dyslexic.” To a child, this translates to, “No matter how hard you try, you’ll never be enough.”

About Dyslexia

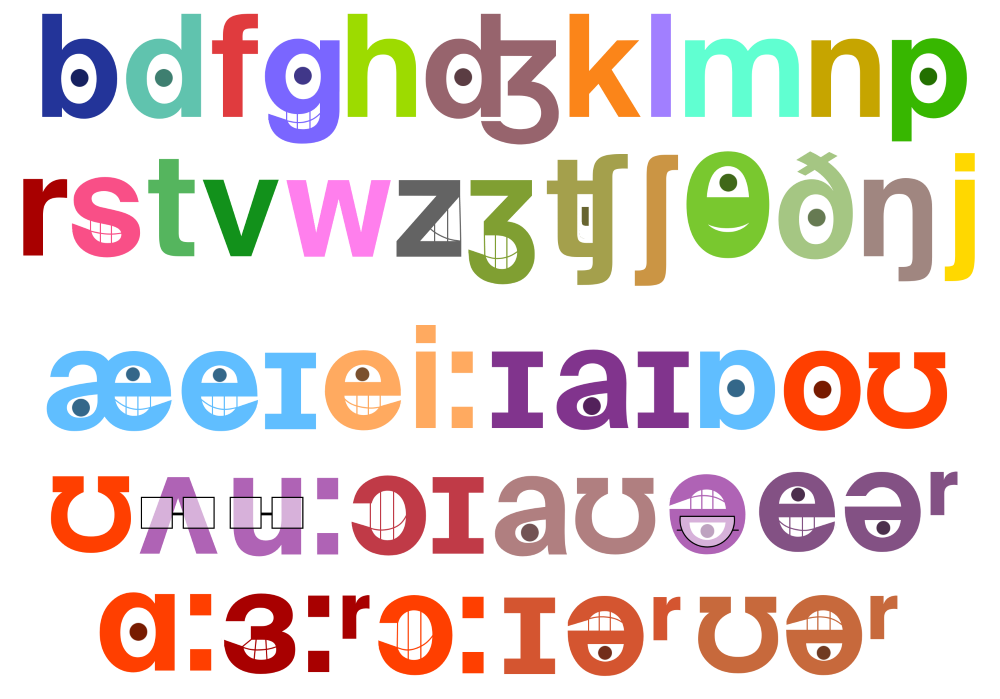

Dyslexia is a learning difference that primarily affects reading, spelling, and writing skills. It’s a neurological condition rooted in difficulties with phonological processing – decoding words, and matching letters to sounds.

Key Characteristics

Reading Difficulties: Trouble recognizing words accurately and fluently. Slow reading speed. Skipping or reversing letters.

Spelling Challenges: Frequent errors. Mixing up letter sequences.

Writing Struggles: Difficulty organizing thoughts. Reversing letters or numbers.

Other Challenges: Trouble remembering sequences (e.g., days of the week). Difficulties with pronunciation or rhyming. Struggles with learning new languages.

What Dyslexia Is Not: Dyslexia is not linked to intelligence. It’s not caused by vision problems, although some individuals perceive text differently. With the right support, accommodations, and understanding, dyslexic individuals thrive. Many exhibit exceptional creativity, problem-solving skills, and out-of-the-box thinking. I’m living proof of that, and I hope to inspire my students to believe the same.